Building memories with Koichi Suzuno

In a renovated warehouse in Kiyosumi Shirakawa, Tokyobike’s newest shop opened its doors on July 10. Dating back almost 60 years, the building was transformed under the direction of Torafu Architects, creating a mixed-use space that builds upon its industrial background. “Renovation is a way of preserving the memories of a place,” explains Torafu co-founder Koichi Suzuno. As the warehouse underwent transformation, another one of Suzuno’s renovations was unfolding on the other side of Tokyo: a three-storey concrete house he would soon call home.

For an architect, living within a space they’ve designed means coming to terms with their work on an intimate level. As their home, the work itself encapsulates various facets of daily life. Shortly after the house’s completion, we paid a visit to Suzuno to gain an insight into the renovation.

It’s mid-morning and Koichi Suzuno is crouched on the carpet, gazing up at the staircase that punctuates his family’s home in Kakinokizaka, Meguro. Concrete planes extend upwards, while light cascades down the white walls and carpet-covered stairs, where Suzuno’s three-year-old cat, Sunny, reclines peacefully. As we move through the house, Suzuno stops to narrate scenes where the elements, some old, some new, resonate in harmony. There’s the stripped-back concrete wall, a feature of the traditional tea room; lustrous hinges on doors with a smoky complexion; and the intersection of materials, from linoleum to carpet and exposed steel, at the base of the stairs. Everything comes with a story of what it was and what it has become, connecting layers of history through the eyes of the architect.

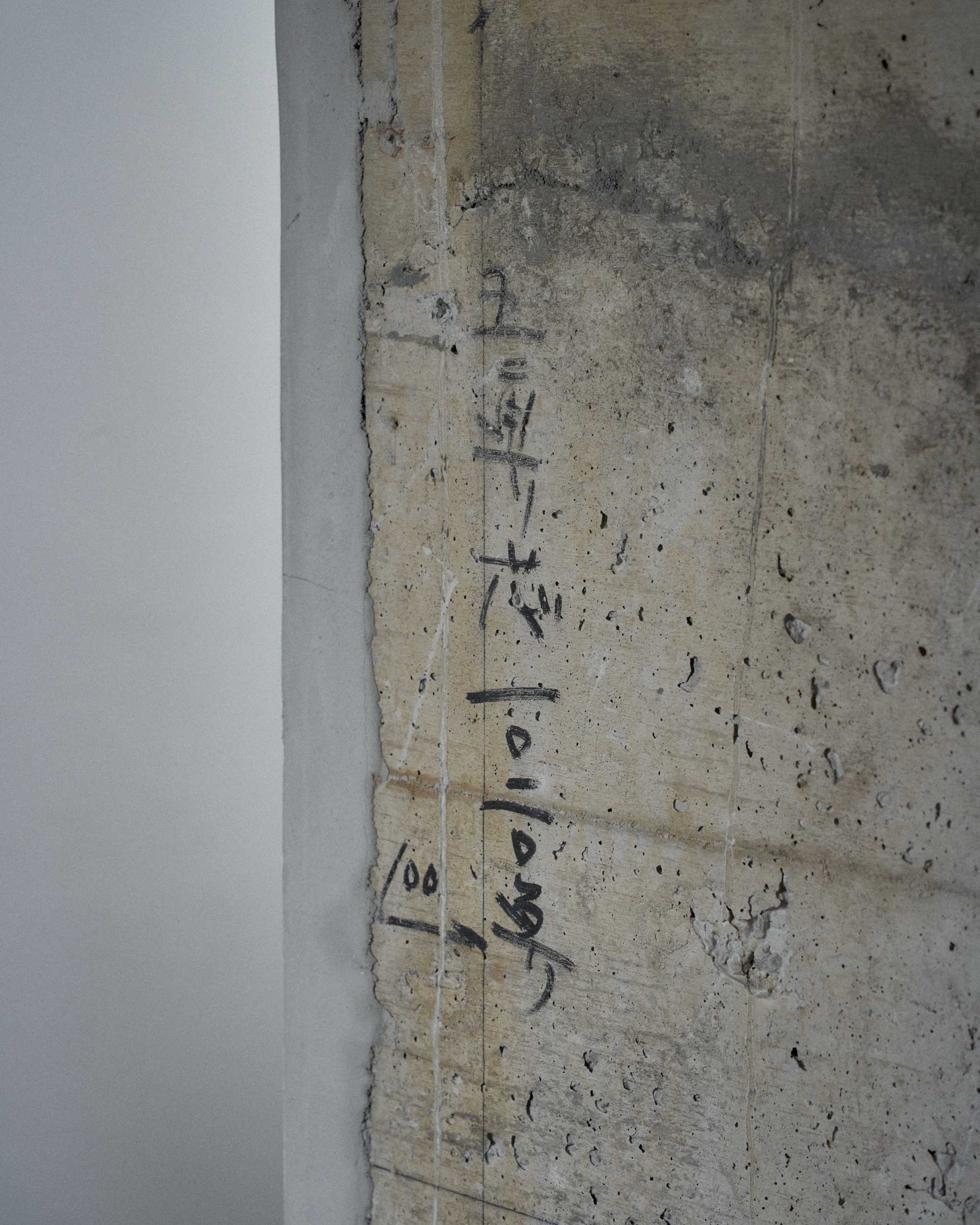

After receiving the keys to the house in late March, Suzuno spent two months on-site with a small team. Even after more than two decades as an architect, his work was unusually hands-on and intuitive: tools in hand; directions chalked on walls and, with a few exceptions, no design drawings.

Removing the internal partitions, fixtures and finishes that had constricted the interior, the structure was allowed to breathe once again. “Oldness can’t simply be created,” says Suzuno. “Humans feel a greater sense of empathy towards materials with a history, rather than shiny new ones.” From rugged beams to conduits, bolts and tile mortar, the remaining elements became features, with simple white walls used to offset the concrete structure, exposed for the first time in nearly four decades. The process also provided a chance to reconnect with the adjacent green strip. A large opening was carved out of the dining room wall to create an engawa-like perch, hovering between inside and out. It’s here that he often spends his mornings, looking out over the terrace greenery.

“While mortar feels a bit artificial,” says Suzuno, running his hand along the contours of an exposed beam. “I’ve come to think of rough concrete as something more natural, almost like the bark of a tree.”

For an architect whose fascination with buildings dates back to his youth, even spending a summer vacation constructing a scale model of his parent’s house, these old materials connect to a long-held interest in the memories buildings contain. Residential, retail or otherwise, his renovations are like collaborations between the past and the present. Architecture never begins with a truly blank canvas; there is always a history to be acknowledged and explored.

Text by Ben Davis

Photo by Daisuke Hashihara